THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES

First edition, 1902

| Chapter 1. |

Mr. Sherlock Holmes |

| Chapter 2. |

The Curse of the Baskervilles |

| Chapter 3. |

The Problem |

| Chapter 4. |

Sir Henry Baskerville |

| Chapter 5. |

Three Broken Threads |

| Chapter 6. |

Baskerville Hall |

| Chapter 7. |

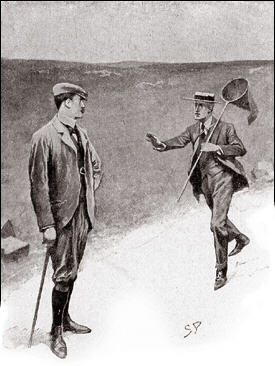

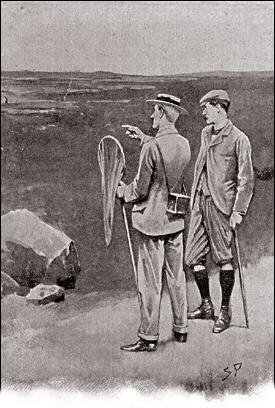

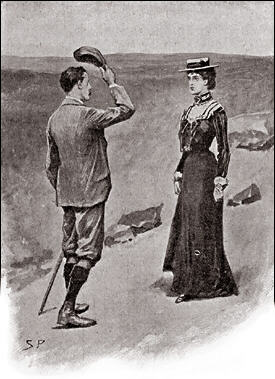

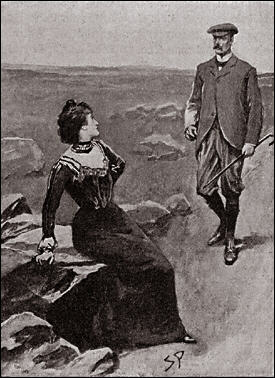

The Stapletons of the Merripit House |

| Chapter 8. |

First Report of Dr. Watson |

| Chapter 9. |

Second Report of Dr. Watson |

| Chapter 10. |

Extract from the Diary of Dr. Watson |

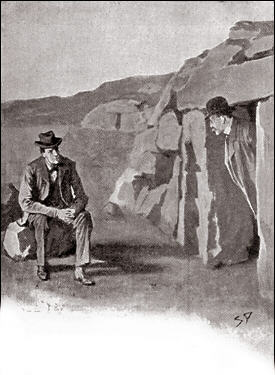

| Chapter 11. |

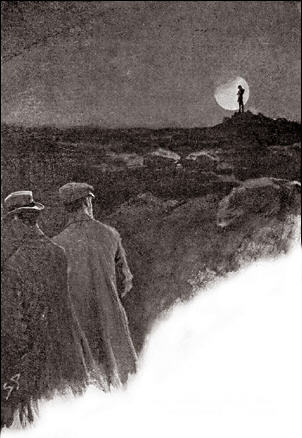

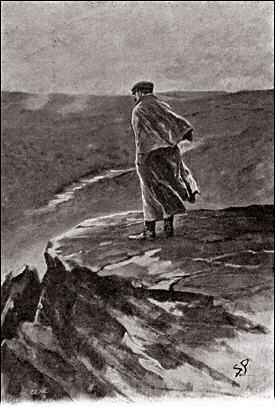

The Man on the Tor |

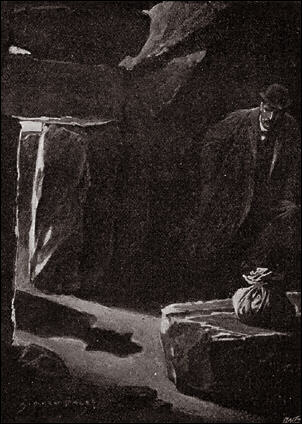

| Chapter 12. |

Death on the Moor |

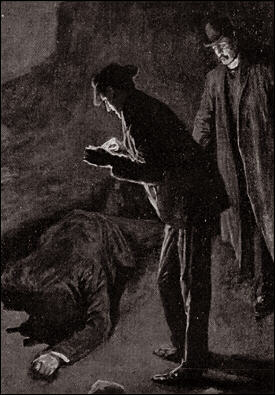

| Chapter 13. |

Fixing the Nets |

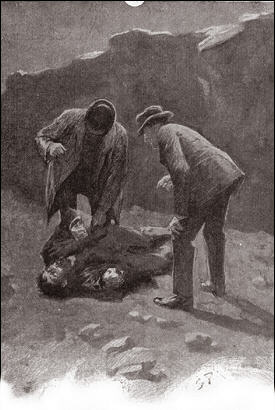

| Chapter 14. |

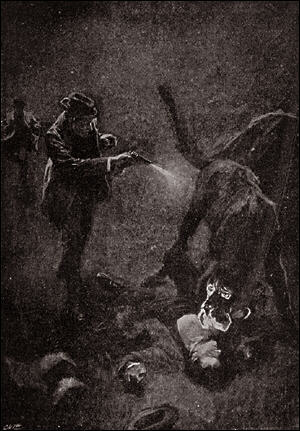

The Hound of the Baskervilles |

| Chapter 15. |

A Retrospection The story was first published monthly in the Strand Magazine, Aug. 1901 - Apr. 1902, with 60 illustrations by Sidney Paget. The first book edition was published on 25 Mar. 1902 by G. Newnes Ltd. in an edition of 25,000 copies. The first American edition by McClure, Phillips & Co. on 15 Apr. 1902 in an edition of 50,000 copies. DEDICATION MY DEAR ROBINSON: It was your account of a west country legend which first suggested the idea of this little tale to my mind. For this, and for the help which you gave me in its evolution, all thanks.

Yours most truly,

|

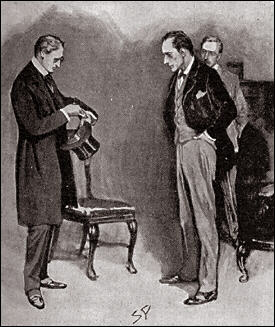

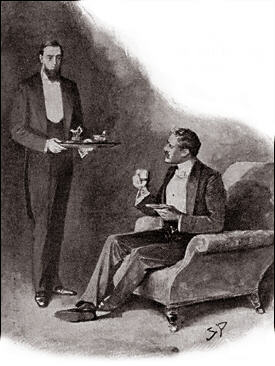

MR. SHERLOCK HOLMES

MR. SHERLOCK HOLMES, who was usually very late in the mornings, save upon those not infrequent occasions when he was up all night, was seated at the

breakfast table. I stood upon the hearth-rug and picked up the stick which our visitor had left behind him the night before. It was a fine, thick piece of wood, bulbous-headed, of the sort

which is known as a “Penang lawyer.” Just under the head was a broad silver band, nearly an inch across. “To James Mortimer, M.R.C.S., from his friends of the C.C.H.,”

was engraved upon it, with the date “1884.” It was just such a stick as the old-fashioned family practitioner used to carry–dignified, solid, and reassuring.

“Well, Watson, what do you make of it?”

Holmes was sitting with his back to me, and I had given him no sign of my occupation.

“How did you know what I was doing? I believe you have eyes in the back of your head.”

“I have, at least, a well-polished, silver-plated coffee-pot in front of me,” said he. “But, tell me, Watson, what do you make of our visitor’s stick? Since we have been

so unfortunate as to miss him and have no notion of his errand, this accidental souvenir becomes of importance. Let me hear you reconstruct the man by an examination of it.”

“I think,” said I, following as far as I could the methods of my companion, “that Dr. Mortimer is a successful, elderly medical man, well-esteemed, since those who know him

give him this mark of their appreciation.”

“Good!” said Holmes. “Excellent!”

“I think also that the probability is in favour of his being a country practitioner who does a great deal of his visiting on foot.”

“Why so?”

“Because this stick, though originally a very handsome one, has been so knocked about that I can hardly imagine a town practitioner carrying it. The thick iron ferrule is worn down, so it

is evident that he has done a great amount of walking with it.”

“Perfectly sound!” said Holmes.

“And then again, there is the ‘friends of the C.C.H.’ I should guess that to be the Something Hunt, the local hunt to whose members he has possibly given some surgical

assistance, and which has made him a small presentation in return.”

“Really, Watson, you excel yourself,” said Holmes, pushing back his chair and lighting a cigarette. “I am bound to say that in all the accounts which you have been so good as

to give of my own small achievements you have habitually underrated your own abilities. It may be that you are not yourself luminous, but you are a conductor of light. Some people without

possessing genius have a remarkable power of stimulating it. I confess, my dear fellow, that I am very much in your debt.”

He had never said as much before, and I must admit that his words gave me keen pleasure, for I had often been piqued by his indifference to my admiration and to the attempts which I had made to

give publicity to his methods. I was proud, too, to think that I had so far mastered his system as to apply it in a way which earned his approval. He now took the stick from my hands and

examined it for a few minutes with his naked eyes. Then with an expression of interest he laid down his cigarette, and, carrying the cane to the window, he looked over it again with a convex

lens.

“Interesting, though elementary,” said he as he returned to his favourite corner of the settee. “There are certainly one or two indications upon the stick. It gives us the basis for several deductions.”

“Has anything escaped me?” I asked with some self-importance. “I trust that there is nothing of consequence which I have overlooked?”

“I am afraid, my dear Watson, that most of your conclusions were erroneous. When I said that you stimulated me I meant, to be frank, that in noting your fallacies I was occasionally guided towards the truth. Not that you are entirely wrong in this instance. The man is certainly a country practitioner. And he walks a good deal.”

“Then I was right.”

“To that extent.”

“But that was all.”

“No, no, my dear Watson, not all–by no means all. I would suggest, for example, that a presentation to a doctor is more likely to come from a hospital than from a hunt, and that when the initials ‘C.C.’ are placed before that hospital the words ‘Charing Cross’ very naturally suggest themselves.”

“You may be right.”

“The probability lies in that direction. And if we take this as a working hypothesis we have a fresh basis from which to start our construction of this unknown visitor.”

“Well, then, supposing that ‘C.C.H.’ does stand for ‘Charing Cross Hospital,’ what further inferences may we draw?”

“Do none suggest themselves? You know my methods. Apply them!”

“I can only think of the obvious conclusion that the man has practised in town before going to the country.”

“I think that we might venture a little farther than this. Look at it in this light. On what occasion would it be most probable that such a presentation would be made? When would his friends unite to give him a pledge of their good will? Obviously at the moment when Dr. Mortimer withdrew from the service of the hospital in order to start in practice for himself. We know there has been a presentation. We believe there has been a change from a town hospital to a country practice. Is it, then, stretching our inference too far to say that the presentation was on the occasion of the change?”

“It certainly seems probable.”

“Now, you will observe that he could not have been on the staff of the hospital, since only a man well-established in a London practice could hold such a position, and such a one would not drift into the country. What was he, then? If he was in the hospital and yet not on the staff he could only have been a house-surgeon or a house-physician–little more than a senior student. And he left five years ago–the date is on the stick. So your grave, middle-aged family practitioner vanishes into thin air, my dear Watson, and there emerges a young fellow under thirty, amiable, unambitious, absent-minded, and the possessor of a favourite dog, which I should describe roughly as being larger than a terrier and smaller than a mastiff.”

I laughed incredulously as Sherlock Holmes leaned back in his settee and blew little wavering rings of smoke up to the ceiling.

“As to the latter part, I have no means of checking you,” said I, “but at least it is not difficult to find out a few particulars about the man’s age and professional career.” From my small medical shelf I took down the Medical Directory and turned up the name. There were several Mortimers, but only one who could be our visitor. I read his record aloud.

- “Mortimer, James, M.R.C.S., 1882, Grimpen, Dartmoor, Devon. House surgeon, from 1882 to 1884, at Charing Cross Hospital. Winner of the Jackson prize for Comparative Pathology, with essay entitled ‘Is Disease a Reversion?’ Corresponding member of the Swedish Pathological Society. Author of ‘Some Freaks of Atavism’ (Lancet, 1882). ‘Do We Progress?’ (Journal of Psychology, March, 1883). Medical Officer for the parishes of Grimpen, Thorsley, and High Barrow.”

“No mention of that local hunt, Watson,” said Holmes with a mischievous smile, “but a country doctor, as you very astutely observed. I think that I am fairly justified in my

inferences. As to the adjectives, I said, if I remember right, amiable, unambitious, and absent-minded. It is my experience that it is only an amiable man in this world who receives

testimonials, only an unambitious one who abandons a London career for the country, and only an absent-minded one who leaves his stick and not his visiting-card after waiting an hour in your

room.”

“And the dog?”

“Has been in the habit of carrying this stick behind his master. Being a heavy stick the dog has held it tightly by the middle, and the marks of his teeth are very plainly visible. The

dog’s jaw, as shown in the space between these marks, is too broad in my opinion for a terrier and not broad enough for a mastiff. It may have been–yes, by Jove, it is a

curly-haired spaniel.”

He had risen and paced the room as he spoke. Now he halted in the recess of the window. There was such a ring of conviction in his voice that I glanced up in surprise.

“My dear fellow, how can you possibly be so sure of that?”

“For the very simple reason that I see the dog himself on our very door-step, and there is the ring of its owner. Don’t move, I beg you, Watson. He is a professional brother of

yours, and your presence may be of assistance to me. Now is the dramatic moment of fate, Watson, when you hear a step upon the stair which is walking into your life, and you know not whether

for good or ill. What does Dr. James Mortimer, the man of science, ask of Sherlock Holmes, the specialist in crime? Come in!”

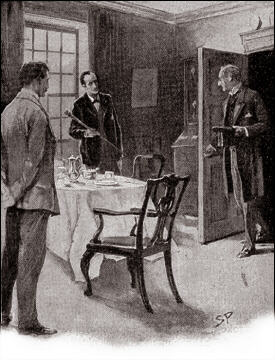

The appearance of our visitor was a surprise to me, since I had expected a typical country practitioner. He was a very tall, thin man, with a long nose like a beak, which jutted out between two

keen, gray eyes, set closely together and sparkling brightly from behind a pair of gold-rimmed glasses. He was clad in a professional but rather slovenly fashion, for his frock-coat was dingy

and his trousers frayed. Though young, his long back was already bowed, and he walked with a forward thrust of his head and a general air of peering benevolence. As he entered his eyes fell

upon the stick in Holmes’s hand, and he ran towards it with an exclamation of joy. “I am so very glad,” said he. “I was not sure whether I had left it here or in the

Shipping Office. I would not lose that stick for the world.”

“A presentation, I see,” said Holmes.

“Yes, sir.”

“From Charing Cross Hospital?”

“From one or two friends there on the occasion of my marriage.”

“Dear, dear, that’s bad!” said Holmes, shaking his head.

Dr. Mortimer blinked through his glasses in mild astonishment.

“Why was it bad?”

“Only that you have disarranged our little deductions. Your marriage, you say?”

“Yes, sir. I married, and so left the hospital, and with it all hopes of a consulting practice. It was necessary to make a home of my own.”

“Come, come, we are not so far wrong, after all,” said Holmes. “And now, Dr. James Mortimer– –”

“Mister, sir, Mister–a humble M.R.C.S.”

“And a man of precise mind, evidently.”

“A dabbler in science, Mr. Holmes, a picker up of shells on the shores of the great unknown ocean. I presume that it is Mr. Sherlock Holmes whom I am addressing and not–

–”

“No, this is my friend Dr. Watson.”

“Glad to meet you, sir. I have heard your name mentioned in connection with that of your friend. You interest me very much, Mr. Holmes. I had hardly expected so dolichocephalic a skull or

such well-marked supra-orbital development. Would you have any objection to my running my finger along your parietal fissure? A cast of your skull, sir, until the original is available, would

be an ornament to any anthropological museum. It is not my intention to be fulsome, but I confess that I covet your skull.”

Sherlock Holmes waved our strange visitor into a chair. “You are an enthusiast in your line of thought, I perceive, sir, as I am in mine,” said he. “I observe from your

forefinger that you make your own cigarettes. Have no hesitation in lighting one.”

The man drew out paper and tobacco and twirled the one up in the other with surprising dexterity. He had long, quivering fingers as agile and restless as the antennae of an insect.

Holmes was silent, but his little darting glances showed me the interest which he took in our curious companion.

“I presume, sir,” said he at last, “that it was not merely for the purpose of examining my skull that you have done me the honour to call here last night and again

to-day?”

“No, sir, no; though I am happy to have had the opportunity of doing that as well. I came to you, Mr. Holmes, because I recognized that I am myself an unpractical man and because I am

suddenly confronted with a most serious and extraordinary problem. Recognizing, as I do, that you are the second highest expert in Europe– –”

“Indeed, sir! May I inquire who has the honour to be the first?” asked Holmes with some asperity.

“To the man of precisely scientific mind the work of Monsieur Bertillon must always appeal strongly.”

“Then had you not better consult him?”

“I said, sir, to the precisely scientific mind. But as a practical man of affairs it is acknowledged that you stand alone. I trust, sir, that I have not inadvertently–

–”

“Just a little,” said Holmes. “I think, Dr. Mortimer, you would do wisely if without more ado you would kindly tell me plainly what the exact nature of the problem is in which

you demand my assistance.”

THE CURSE OF THE BASKERVILLES

“I HAVE in my pocket a manuscript,” said Dr. James Mortimer.

“I observed it as you entered the room,” said Holmes.

“It is an old manuscript.”

“Early eighteenth century, unless it is a forgery.”

“How can you say that, sir?”

“You have presented an inch or two of it to my examination all the time that you have been talking. It would be a poor expert who could not give the date of a document within a decade or

so. You may possibly have read my little monograph upon the subject. I put that at 1730.”

“The exact date is 1742.” Dr. Mortimer drew it from his breast-pocket. “This family paper was committed to my care by Sir Charles Baskerville, whose sudden and tragic death

some three months ago created so much excitement in Devonshire. I may say that I was his personal friend as well as his medical attendant. He was a strong-minded man, sir, shrewd, practical,

and as unimaginative as I am myself. Yet he took this document very seriously, and his mind was prepared for just such an end as did eventually overtake him.”

Holmes stretched out his hand for the manuscript and flattened it upon his knee.

“You will observe, Watson, the alternative use of the long s and the short. It is one of several indications which enabled me to fix the date.”

I looked over his shoulder at the yellow paper and the faded script. At the head was written: “Baskerville Hall,” and below, in large, scrawling figures: “1742.”

“It appears to be a statement of some sort.”

“Yes, it is a statement of a certain legend which runs in the Baskerville family.”

“But I understand that it is something more modern and practical upon which you wish to consult me?”

“Most modern. A most practical, pressing matter, which must be decided within twenty-four hours. But the manuscript is short and is intimately connected with the affair. With your

permission I will read it to you.”

Holmes leaned back in his chair, placed his finger-tips together, and closed his eyes, with an air of resignation. Dr. Mortimer turned the manuscript to the light and read in a high, crackling voice the following curious, old-world narrative:

-

Of the origin of the Hound of the Baskervilles there have been many statements, yet as I come in a direct line from Hugo Baskerville, and as I had the story from my father, who also had it

from his, I have set it down with all belief that it occurred even as is here set forth. And I would have you believe, my sons, that the same Justice which punishes sin may also most

graciously forgive it, and that no ban is so heavy but that by prayer and repentance it may be removed. Learn then from this story not to fear the fruits of the past, but rather to be

circumspect in the future, that those foul passions whereby our family has suffered so grievously may not again be loosed to our undoing.

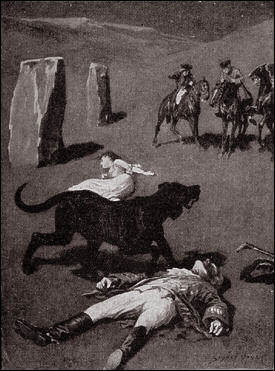

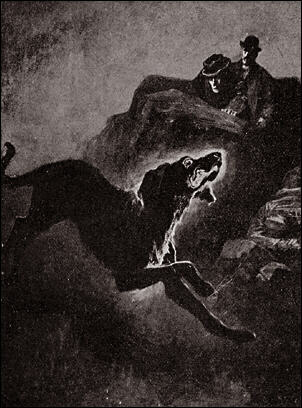

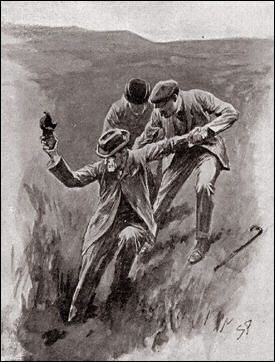

“Know then that in the time of the Great Rebellion (the history of which by the learned Lord Clarendon I most earnestly commend to your attention) this Manor of Baskerville was held by Hugo of that name, nor can it be gainsaid that he was a most wild, profane, and godless man. This, in truth, his neighbours might have pardoned, seeing that saints have never flourished in those parts, but there was in him a certain wanton and cruel humour which made his name a byword through the West. It chanced that this Hugo came to love (if, indeed, so dark a passion may be known under so bright a name) the daughter of a yeoman who held lands near the Baskerville estate. But the young maiden, being discreet and of good repute, would ever avoid him, for she feared his evil name. So it came to pass that one Michaelmas this Hugo, with five or six of his idle and wicked companions, stole down upon the farm and carried off the maiden, her father and brothers being from home, as he well knew. When they had brought her to the Hall the maiden was placed in an upper chamber, while Hugo and his friends sat down to a long carouse, as was their nightly custom. Now, the poor lass upstairs was like to have her wits turned at the singing and shouting and terrible oaths which came up to her from below, for they say that the words used by Hugo Baskerville, when he was in wine, were such as might blast the man who said them. At last in the stress of her fear she did that which might have daunted the bravest or most active man, for by the aid of the growth of ivy which covered (and still covers) the south wall she came down from under the eaves, and so homeward across the moor, there being three leagues betwixt the Hall and her father’s farm.

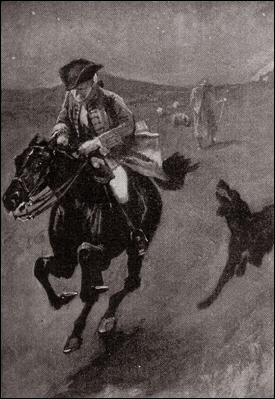

“It chanced that some little time later Hugo left his guests to carry food and drink–with other worse things, perchance–to his captive, and so found the cage empty and the bird escaped. Then, as it would seem, he became as one that hath a devil, for, rushing down the stairs into the dining-hall, he sprang upon the great table, flagons and trenchers flying before him, and he cried aloud before all the company that he would that very night render his body and soul to the Powers of Evil if he might but overtake the wench. And while the revellers stood aghast at the fury of the man, one more wicked or, it may be, more drunken than the rest, cried out that they should put the hounds upon her. Whereat Hugo ran from the house, crying to his grooms that they should saddle his mare and unkennel the pack, and giving the hounds a kerchief of the maid’s, he swung them to the line, and so off full cry in the moonlight over the moor.

“Now, for some space the revellers stood agape, unable to understand all that had been done in such haste. But anon their bemused wits awoke to the nature of the deed which was like to be done upon the moorlands. Everything was now in an uproar, some calling for their pistols, some for their horses, and some for another flask of wine. But at length some sense came back to their crazed minds, and the whole of them, thirteen in number, took horse and started in pursuit. The moon shone clear above them, and they rode swiftly abreast, taking that course which the maid must needs have taken if she were to reach her own home. - “They had gone a mile or two when they passed one of the night shepherds upon the moorlands, and they cried to him to know if he had seen the hunt. And the man, as the story goes, was so crazed with fear that he could scarce speak, but at last he said that he had indeed seen the unhappy maiden, with the hounds upon her track. ‘But I have seen more than that,’ said he, ‘for Hugo Baskerville passed me upon his black mare, and there ran mute behind him such a hound of hell as God forbid should ever be at my heels.’ So the drunken squires cursed the shepherd and rode onward. But soon their skins turned cold, for there came a galloping across the moor, and the black mare, dabbled with white froth, went past with trailing bridle and empty saddle. Then the revellers rode close together, for a great fear was on them, but they still followed over the moor, though each, had he been alone, would have been right glad to have turned his horse’s head. Riding slowly in this fashion they came at last upon the hounds. These, though known for their valour and their breed, were whimpering in a cluster at the head of a deep dip or goyal, as we call it, upon the moor, some slinking away and some, with starting hackles and staring eyes, gazing down the narrow valley before them.

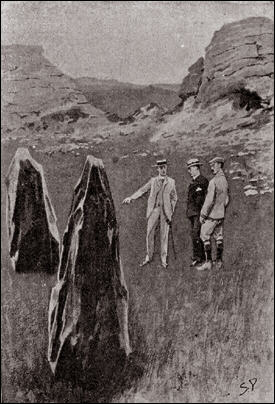

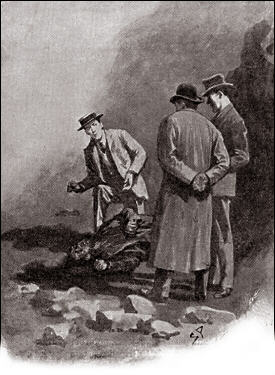

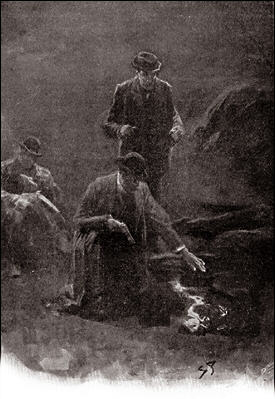

- “The company had come to a halt, more sober men, as you may guess, than when they started. The most of them would by no means advance, but three of them, the boldest, or it may be the most drunken, rode forward down the goyal. Now, it opened into a broad space in which stood two of those great stones, still to be seen there, which were set by certain forgotten peoples in the days of old. The moon was shining bright upon the clearing, and there in the centre lay the unhappy maid where she had fallen, dead of fear and of fatigue. But it was not the sight of her body, nor yet was it that of the body of Hugo Baskerville lying near her, which raised the hair upon the heads of these three dare-devil roysterers, but it was that, standing over Hugo, and plucking at his throat, there stood a foul thing, a great, black beast, shaped like a hound, yet larger than any hound that ever mortal eye has rested upon. And even as they looked the thing tore the throat out of Hugo Baskerville, on which, as it turned its blazing eyes and dripping jaws upon them, the three shrieked with fear and rode for dear life, still screaming, across the moor. One, it is said, died that very night of what he had seen, and the other twain were but broken men for the rest of their days.

-

“Such is the tale, my sons, of the coming of the hound which is said to have plagued the family so sorely ever since. If I have set it down it is because that which is clearly known

hath less terror than that which is but hinted at and guessed. Nor can it be denied that many of the family have been unhappy in their deaths, which have been sudden, bloody, and mysterious.

Yet may we shelter ourselves in the infinite goodness of Providence, which would not forever punish the innocent beyond that third or fourth generation which is threatened in Holy Writ. To

that Providence, my sons, I hereby commend you, and I counsel you by way of caution to forbear from crossing the moor in those dark hours when the powers of evil are exalted.

“[This from Hugo Baskerville to his sons Rodger and John, with instructions that they say nothing thereof to their sister Elizabeth.]”

When Dr. Mortimer had finished reading this singular narrative he pushed his spectacles up on his forehead and stared across at Mr. Sherlock Holmes. The latter yawned and tossed the end of his

cigarette into the fire.

“Well?” said he.

“Do you not find it interesting?”

“To a collector of fairy tales.”

Dr. Mortimer drew a folded newspaper out of his pocket.

“Now, Mr. Holmes, we will give you something a little more recent. This is the Devon County Chronicle of May 14th of this year. It is a short account of the facts elicited at the

death of Sir Charles Baskerville which occurred a few days before that date.”

My friend leaned a little forward and his expression became intent. Our visitor readjusted his glasses and began:

-

“The recent sudden death of Sir Charles Baskerville, whose name has been mentioned as the probable Liberal candidate for Mid-Devon at the next election, has cast a gloom over the

county. Though Sir Charles had resided at Baskerville Hall for a comparatively short period his amiability of character and extreme generosity had won the affection and respect of all who had

been brought into contact with him. In these days of nouveaux riches it is refreshing to find a case where the scion of an old county family which has fallen upon evil days is able to make

his own fortune and to bring it back with him to restore the fallen grandeur of his line. Sir Charles, as is well known, made large sums of money in South African speculation. More wise than

those who go on until the wheel turns against them, he realized his gains and returned to England with them. It is only two years since he took up his residence at Baskerville Hall, and it is

common talk how large were those schemes of reconstruction and improvement which have been interrupted by his death. Being himself childless, it was his openly expressed desire that the whole

countryside should, within his own lifetime, profit by his good fortune, and many will have personal reasons for bewailing his untimely end. His generous donations to local and county

charities have been frequently chronicled in these columns.

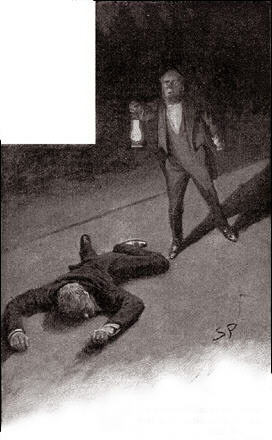

“The circumstances connected with the death of Sir Charles cannot be said to have been entirely cleared up by the inquest, but at least enough has been done to dispose of those rumours to which local superstition has given rise. There is no reason whatever to suspect foul play, or to imagine that death could be from any but natural causes. Sir Charles was a widower, and a man who may be said to have been in some ways of an eccentric habit of mind. In spite of his considerable wealth he was simple in his personal tastes, and his indoor servants at Baskerville Hall consisted of a married couple named Barrymore, the husband acting as butler and the wife as housekeeper. Their evidence, corroborated by that of several friends, tends to show that Sir Charles’s health has for some time been impaired, and points especially to some affection of the heart, manifesting itself in changes of colour, breathlessness, and acute attacks of nervous depression. Dr. James Mortimer, the friend and medical attendant of the deceased, has given evidence to the same effect.

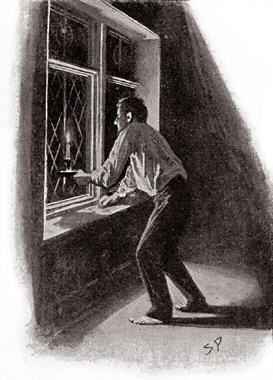

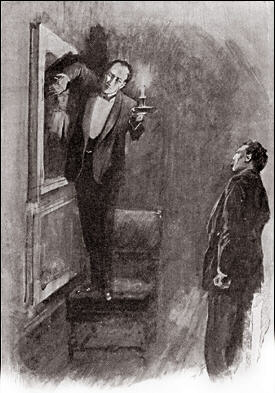

- “The facts of the case are simple. Sir Charles Baskerville was in the habit every night before going to bed of walking down the famous yew alley of Baskerville Hall. The evidence of the Barrymores shows that this had been his custom. On the fourth of May Sir Charles had declared his intention of starting next day for London, and had ordered Barrymore to prepare his luggage. That night he went out as usual for his nocturnal walk, in the course of which he was in the habit of smoking a cigar. He never returned. At twelve o’clock Barrymore, finding the hall door still open, became alarmed, and, lighting a lantern, went in search of his master. The day had been wet, and Sir Charles’s footmarks were easily traced down the alley. Halfway down this walk there is a gate which leads out on to the moor. There were indications that Sir Charles had stood for some little time here. He then proceeded down the alley, and it was at the far end of it that his body was discovered. One fact which has not been explained is the statement of Barrymore that his master’s footprints altered their character from the time that he passed the moor-gate, and that he appeared from thence onward to have been walking upon his toes. One Murphy, a gipsy horse-dealer, was on the moor at no great distance at the time, but he appears by his own confession to have been the worse for drink. He declares that he heard cries but is unable to state from what direction they came. No signs of violence were to be discovered upon Sir Charles’s person, and though the doctor’s evidence pointed to an almost incredible facial distortion–so great that Dr. Mortimer refused at first to believe that it was indeed his friend and patient who lay before him–it was explained that that is a symptom which is not unusual in cases of dyspnoea and death from cardiac exhaustion. This explanation was borne out by the post-mortem examination, which showed long-standing organic disease, and the coroner’s jury returned a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence. It is well that this is so, for it is obviously of the utmost importance that Sir Charles’s heir should settle at the Hall and continue the good work which has been so sadly interrupted. Had the prosaic finding of the coroner not finally put an end to the romantic stories which have been whispered in connection with the affair, it might have been difficult to find a tenant for Baskerville Hall. It is understood that the next of kin is Mr. Henry Baskerville, if he be still alive, the son of Sir Charles Baskerville’s younger brother. The young man when last heard of was in America, and inquiries are being instituted with a view to informing him of his good fortune.”

Dr. Mortimer refolded his paper and replaced it in his pocket.

“Those are the public facts, Mr. Holmes, in connection with the death of Sir Charles Baskerville.”

“I must thank you,” said Sherlock Holmes, “for calling my attention to a case which certainly presents some features of interest. I had observed some newspaper comment at the

time, but I was exceedingly preoccupied by that little affair of the Vatican cameos, and in my anxiety to oblige the Pope I lost touch with several interesting English cases. This article, you

say, contains all the public facts?”

“It does.”

“Then let me have the private ones.” He leaned back, put his finger-tips together, and assumed his most impassive and judicial expression.

“In doing so,” said Dr. Mortimer, who had begun to show signs of some strong emotion, “I am telling that which I have not confided to anyone. My motive for withholding it from

the coroner’s inquiry is that a man of science shrinks from placing himself in the public position of seeming to indorse a popular superstition. I had the further motive that Baskerville

Hall, as the paper says, would certainly remain untenanted if anything were done to increase its already rather grim reputation. For both these reasons I thought that I was justified in telling

rather less than I knew, since no practical good could result from it, but with you there is no reason why I should not be perfectly frank.

“The moor is very sparsely inhabited, and those who live near each other are thrown very much together. For this reason I saw a good deal of Sir Charles Baskerville. With the exception of

Mr. Frankland, of Lafter Hall, and Mr. Stapleton, the naturalist, there are no other men of education within many miles. Sir Charles was a retiring man, but the chance of his illness brought us

together, and a community of interests in science kept us so. He had brought back much scientific information from South Africa, and many a charming evening we have spent together discussing

the comparative anatomy of the Bushman and the Hottentot.

“Within the last few months it became increasingly plain to me that Sir Charles’s nervous system was strained to the breaking point. He had taken this legend which I have read you

exceedingly to heart–so much so that, although he would walk in his own grounds, nothing would induce him to go out upon the moor at night. Incredible as it may appear to you, Mr. Holmes,

he was honestly convinced that a dreadful fate overhung his family, and certainly the records which he was able to give of his ancestors were not encouraging. The idea of some ghastly presence

constantly haunted him, and on more than one occasion he has asked me whether I had on my medical journeys at night ever seen any strange creature or heard the baying of a hound. The latter

question he put to me several times, and always with a voice which vibrated with excitement.

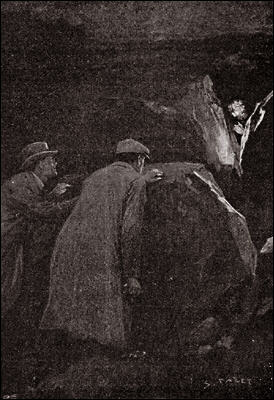

“I can well remember driving up to his house in the evening, some three weeks before the fatal event. He chanced to be at his hall door. I had descended from my gig and was standing in

front of him, when I saw his eyes fix themselves over my shoulder and stare past me with an expression of the most dreadful horror. I whisked round and had just time to catch a glimpse of

something which I took to be a large black calf passing at the head of the drive. So excited and alarmed was he that I was compelled to go down to the spot where the animal had been and look

around for it. It was gone, however, and the incident appeared to make the worst impression upon his mind. I stayed with him all the evening, and it was on that occasion, to explain the emotion

which he had shown, that he confided to my keeping that narrative which I read to you when first I came. I mention this small episode because it assumes some importance in view of the tragedy

which followed, but I was convinced at the time that the matter was entirely trivial and that his excitement had no justification.

“It was at my advice that Sir Charles was about to go to London. His heart was, I knew, affected, and the constant anxiety in which he lived, however chimerical the cause of it might be,

was evidently having a serious effect upon his health. I thought that a few months among the distractions of town would send him back a new man. Mr. Stapleton, a mutual friend who was much

concerned at his state of health, was of the same opinion. At the last instant came this terrible catastrophe.

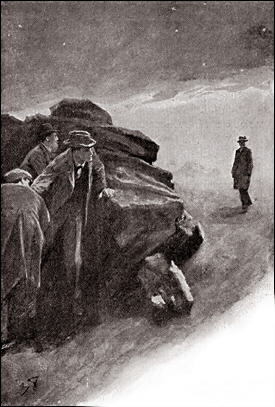

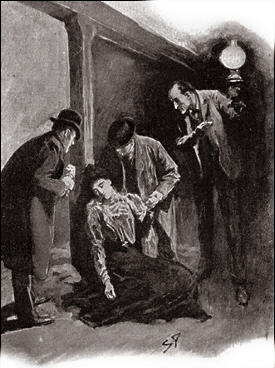

“On the night of Sir Charles’s death Barrymore the butler, who made the discovery, sent Perkins the groom on horseback to me, and as I was sitting up late I was able to reach

Baskerville Hall within an hour of the event. I checked and corroborated all the facts which were mentioned at the inquest. I followed the footsteps down the yew alley, I saw the spot at the

moor-gate where he seemed to have waited, I remarked the change in the shape of the prints after that point, I noted that there were no other footsteps save those of Barrymore on the soft

gravel, and finally I carefully examined the body, which had not been touched until my arrival. Sir Charles lay on his face, his arms out, his fingers dug into the ground, and his features

convulsed with some strong emotion to such an extent that I could hardly have sworn to his identity. There was certainly no physical injury of any kind. But one false statement was made by

Barrymore at the inquest. He said that there were no traces upon the ground round the body. He did not observe any. But I did–some little distance off, but fresh and clear.”

“Footprints?”

“Footprints.”

“A man’s or a woman’s?”

Dr. Mortimer looked strangely at us for an instant, and his voice sank almost to a whisper as he answered:

“Mr. Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!”

THE PROBLEM

I CONFESS that at these words a shudder passed through me. There was a thrill in the doctor’s voice which showed that he was himself deeply moved by that which he told us. Holmes leaned forward in his excitement and his eyes had the hard, dry glitter which shot from them when he was keenly interested.

“You saw this?”

“As clearly as I see you.”

“And you said nothing?”

“What was the use?”

“How was it that no one else saw it?”

“The marks were some twenty yards from the body and no one gave them a thought. I don’t suppose I should have done so had I not known this legend.”

“There are many sheep-dogs on the moor?”

“No doubt, but this was no sheep-dog.”

“You say it was large?”

“Enormous.”

“But it had not approached the body?”

“No.”

“What sort of night was it?”

“Damp and raw.”

“But not actually raining?”

“No.”

“What is the alley like?”

“There are two lines of old yew hedge, twelve feet high and impenetrable. The walk in the centre is about eight feet across.”

“Is there anything between the hedges and the walk?”

“Yes, there is a strip of grass about six feet broad on either side.”

“I understand that the yew hedge is penetrated at one point by a gate?”

“Yes, the wicket-gate which leads on to the moor.”

“Is there any other opening?”

“None.”

“So that to reach the yew alley one either has to come down it from the house or else to enter it by the moor-gate?”

“There is an exit through a summer-house at the far end.”

“Had Sir Charles reached this?”

“No; he lay about fifty yards from it.”

“Now, tell me, Dr. Mortimer–and this is important–the marks which you saw were on the path and not on the grass?”

“No marks could show on the grass.”

“Were they on the same side of the path as the moor-gate?”

“Yes; they were on the edge of the path on the same side as the moor-gate.”

“You interest me exceedingly. Another point. Was the wicket-gate closed?”

“Closed and padlocked.”

“How high was it?”

“About four feet high.”

“Then anyone could have got over it?”

“Yes.”

“And what marks did you see by the wicket-gate?”

“None in particular.”

“Good heaven! Did no one examine?”

“Yes, I examined, myself.”

“And found nothing?”

“It was all very confused. Sir Charles had evidently stood there for five or ten minutes.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because the ash had twice dropped from his cigar.”

“Excellent! This is a colleague, Watson, after our own heart. But the marks?”

“He had left his own marks all over that small patch of gravel. I could discern no others.”

Sherlock Holmes struck his hand against his knee with an impatient gesture.

“If I had only been there!” he cried. “It is evidently a case of extraordinary interest, and one which presented immense opportunities to the scientific expert. That gravel

page upon which I might have read so much has been long ere this smudged by the rain and defaced by the clogs of curious peasants. Oh, Dr. Mortimer, Dr. Mortimer, to think that you should not

have called me in! You have indeed much to answer for.”

“I could not call you in, Mr. Holmes, without disclosing these facts to the world, and I have already given my reasons for not wishing to do so. Besides, besides–

–”

“Why do you hesitate?”

“There is a realm in which the most acute and most experienced of detectives is helpless.”

“You mean that the thing is supernatural?”

“I did not positively say so.”

“No, but you evidently think it.”

“Since the tragedy, Mr. Holmes, there have come to my ears several incidents which are hard to reconcile with the settled order of Nature.”

“For example?”

“I find that before the terrible event occurred several people had seen a creature upon the moor which corresponds with this Baskerville demon, and which could not possibly be any animal

known to science. They all agreed that it was a huge creature, luminous, ghastly, and spectral. I have cross-examined these men, one of them a hard-headed countryman, one a farrier, and one a

moorland farmer, who all tell the same story of this dreadful apparition, exactly corresponding to the hell-hound of the legend. I assure you that there is a reign of terror in the district,

and that it is a hardy man who will cross the moor at night.”

“And you, a trained man of science, believe it to be supernatural?”

“I do not know what to believe.”

Holmes shrugged his shoulders.

“I have hitherto confined my investigations to this world,” said he. “In a modest way I have combated evil, but to take on the Father of Evil himself would, perhaps, be too

ambitious a task. Yet you must admit that the footmark is material.”

“The original hound was material enough to tug a man’s throat out, and yet he was diabolical as well.”

“I see that you have quite gone over to the supernaturalists. But now, Dr. Mortimer, tell me this. If you hold these views, why have you come to consult me at all? You tell me in the same

breath that it is useless to investigate Sir Charles’s death, and that you desire me to do it.”

“I did not say that I desired you to do it.”

“Then, how can I assist you?”

“By advising me as to what I should do with Sir Henry Baskerville, who arrives at Waterloo Station”–Dr. Mortimer looked at his watch–“in exactly one hour and a

quarter.”

“He being the heir?”

“Yes. On the death of Sir Charles we inquired for this young gentleman and found that he had been farming in Canada. From the accounts which have reached us he is an excellent fellow in

every way. I speak now not as a medical man but as a trustee and executor of Sir Charles’s will.”

“There is no other claimant, I presume?”

“None. The only other kinsman whom we have been able to trace was Rodger Baskerville, the youngest of three brothers of whom poor Sir Charles was the elder. The second brother, who died

young, is the father of this lad Henry. The third, Rodger, was the black sheep of the family. He came of the old masterful Baskerville strain and was the very image, they tell me, of the family

picture of old Hugo. He made England too hot to hold him, fled to Central America, and died there in 1876 of yellow fever. Henry is the last of the Baskervilles. In one hour and five minutes I

meet him at Waterloo Station. I have had a wire that he arrived at Southampton this morning. Now, Mr. Holmes, what would you advise me to do with him?”

“Why should he not go to the home of his fathers?”

“It seems natural, does it not? And yet, consider that every Baskerville who goes there meets with an evil fate. I feel sure that if Sir Charles could have spoken with me before his death

he would have warned me against bringing this, the last of the old race, and the heir to great wealth, to that deadly place. And yet it cannot be denied that the prosperity of the whole poor,

bleak countryside depends upon his presence. All the good work which has been done by Sir Charles will crash to the ground if there is no tenant of the Hall. I fear lest I should be swayed too

much by my own obvious interest in the matter, and that is why I bring the case before you and ask for your advice.”

Holmes considered for a little time.

“Put into plain words, the matter is this,” said he. “In your opinion there is a diabolical agency which makes Dartmoor an unsafe abode for a Baskerville–that is your

opinion?”

“At least I might go the length of saying that there is some evidence that this may be so.”

“Exactly. But surely, if your supernatural theory be correct, it could work the young man evil in London as easily as in Devonshire. A devil with merely local powers like a parish vestry

would be too inconceivable a thing.”

“You put the matter more flippantly, Mr. Holmes, than you would probably do if you were brought into personal contact with these things. Your advice, then, as I understand it, is that the

young man will be as safe in Devonshire as in London. He comes in fifty minutes. What would you recommend?”

“I recommend, sir, that you take a cab, call off your spaniel who is scratching at my front door, and proceed to Waterloo to meet Sir Henry Baskerville.”

“And then?”

“And then you will say nothing to him at all until I have made up my mind about the matter.”

“How long will it take you to make up your mind?”

“Twenty-four hours. At ten o’clock to-morrow, Dr. Mortimer, I will be much obliged to you if you will call upon me here, and it will be of help to me in my plans for the future if

you will bring Sir Henry Baskerville with you.”

“I will do so, Mr. Holmes.” He scribbled the appointment on his shirt-cuff and hurried off in his strange, peering, absent-minded fashion. Holmes stopped him at the head of the stair.

“Only one more question, Dr. Mortimer. You say that before Sir Charles Baskerville’s death several people saw this apparition upon the moor?”

“Three people did.”

“Did any see it after?”

“I have not heard of any.”

“Thank you. Good-morning.”

Holmes returned to his seat with that quiet look of inward satisfaction which meant that he had a congenial task before him.

“Going out, Watson?”

“Unless I can help you.”

“No, my dear fellow, it is at the hour of action that I turn to you for aid. But this is splendid, really unique from some points of view. When you pass Bradley’s, would you ask him to send up a pound of the strongest shag tobacco? Thank you. It would be as well if you could make it convenient not to return before evening. Then I should be very glad to compare impressions as to this most interesting problem which has been submitted to us this morning.”

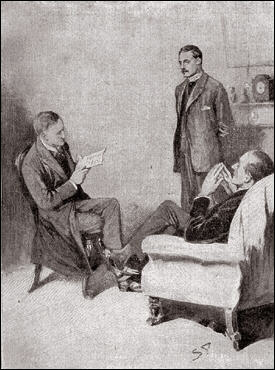

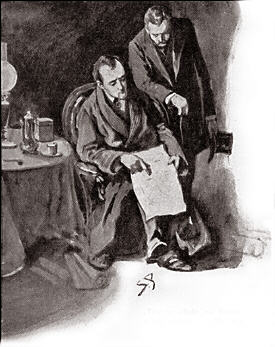

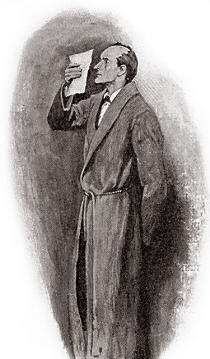

I knew that seclusion and solitude were very necessary for my friend in those hours of intense mental concentration during which he weighed every particle of evidence, constructed alternative theories, balanced one against the other, and made up his mind as to which points were essential and which immaterial. I therefore spent the day at my club and did not return to Baker Street until evening. It was nearly nine o’clock when I found myself in the sitting-room once more.

My first impression as I opened the door was that a fire had broken out, for the room was so filled with smoke that the light of the lamp upon the table was blurred by it. As I entered, however, my fears were set at rest, for it was the acrid fumes of strong coarse tobacco which took me by the throat and set me coughing. Through the haze I had a vague vision of Holmes in his dressing-gown coiled up in an armchair with his black clay pipe between his lips. Several rolls of paper lay around him.

“Caught cold, Watson?” said he.

“No, it’s this poisonous atmosphere.”

“I suppose it is pretty thick, now that you mention it.”

“Thick! It is intolerable.”

“Open the window, then! You have been at your club all day, I perceive.”

“My dear Holmes!”

“Am I right?”

“Certainly, but how– –?”

He laughed at my bewildered expression.

“There is a delightful freshness about you, Watson, which makes it a pleasure to exercise any small powers which I possess at your expense. A gentleman goes forth on a showery and miry day. He returns immaculate in the evening with the gloss still on his hat and his boots. He has been a fixture therefore all day. He is not a man with intimate friends. Where, then, could he have been? Is it not obvious?”

“Well, it is rather obvious.”

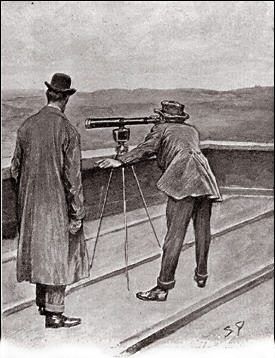

“The world is full of obvious things which nobody by any chance ever observes. Where do you think that I have been?”

“A fixture also.”

“On the contrary, I have been to Devonshire.”

“In spirit?”

“Exactly. My body has remained in this armchair and has, I regret to observe, consumed in my absence two large pots of coffee and an incredible amount of tobacco. After you left I sent down to Stamford’s for the Ordnance map of this portion of the moor, and my spirit has hovered over it all day. I flatter myself that I could find my way about.”

“A large-scale map, I presume?”

“Very large.” He unrolled one section and held it over his knee. “Here you have the particular district which concerns us. That is Baskerville Hall in the middle.”

“With a wood round it?”

“Exactly. I fancy the yew alley, though not marked under that name, must stretch along this line, with the moor, as you perceive, upon the right of it. This small clump of buildings here

is the hamlet of Grimpen, where our friend Dr. Mortimer has his headquarters. Within a radius of five miles there are, as you see, only a very few scattered dwellings. Here is Lafter Hall,

which was mentioned in the narrative. There is a house indicated here which may be the residence of the naturalist–Stapleton, if I remember right, was his name. Here are two moorland

farmhouses, High Tor and Foulmire. Then fourteen miles away the great convict prison of Princetown. Between and around these scattered points extends the desolate, lifeless moor. This, then, is

the stage upon which tragedy has been played, and upon which we may help to play it again.”

“It must be a wild place.”

“Yes, the setting is a worthy one. If the devil did desire to have a hand in the affairs of men– –”

“Then you are yourself inclining to the supernatural explanation.”

“The devil’s agents may be of flesh and blood, may they not? There are two questions waiting for us at the outset. The one is whether any crime has been committed at all; the second

is, what is the crime and how was it committed? Of course, if Dr. Mortimer’s surmise should be correct, and we are dealing with forces outside the ordinary laws of Nature, there is an end

of our investigation. But we are bound to exhaust all other hypotheses before falling back upon this one. I think we’ll shut that window again, if you don’t mind. It is a singular

thing, but I find that a concentrated atmosphere helps a concentration of thought. I have not pushed it to the length of getting into a box to think, but that is the logical outcome of my

convictions. Have you turned the case over in your mind?”

“Yes, I have thought a good deal of it in the course of the day.”

“What do you make of it?”

“It is very bewildering.”

“It has certainly a character of its own. There are points of distinction about it. That change in the footprints, for example. What do you make of that?”

“Mortimer said that the man had walked on tiptoe down that portion of the alley.”

“He only repeated what some fool had said at the inquest. Why should a man walk on tiptoe down the alley?”

“What then?”

“He was running, Watson–running desperately, running for his life, running until he burst his heart and fell dead upon his face.”

“Running from what?”

“There lies our problem. There are indications that the man was crazed with fear before ever he began to run.”

“How can you say that?”

“I am presuming that the cause of his fears came to him across the moor. If that were so, and it seems most probable, only a man who had lost his wits would have run from the

house instead of towards it. If the gipsy’s evidence may be taken as true, he ran with cries for help in the direction where help was least likely to be. Then, again, whom was he waiting

for that night, and why was he waiting for him in the yew alley rather than in his own house?”

“You think that he was waiting for someone?”

“The man was elderly and infirm. We can understand his taking an evening stroll, but the ground was damp and the night inclement. Is it natural that he should stand for five or ten

minutes, as Dr. Mortimer, with more practical sense than I should have given him credit for, deduced from the cigar ash?”

“But he went out every evening.”

“I think it unlikely that he waited at the moor-gate every evening. On the contrary, the evidence is that he avoided the moor. That night he waited there. It was the night before he made

his departure for London. The thing takes shape, Watson. It becomes coherent. Might I ask you to hand me my violin, and we will postpone all further thought upon this business until we have had

the advantage of meeting Dr. Mortimer and Sir Henry Baskerville in the morning.”

SIR HENRY BASKERVILLE

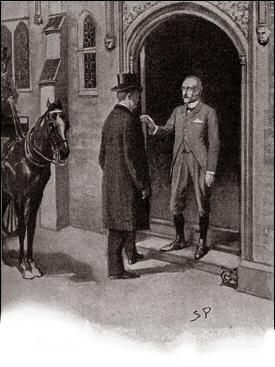

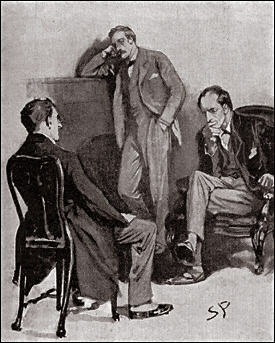

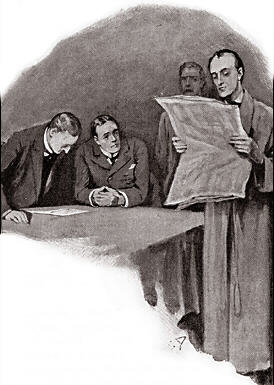

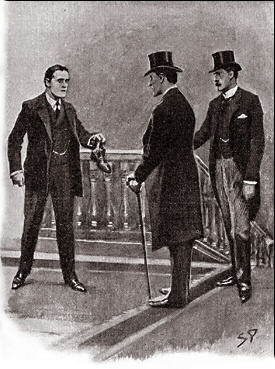

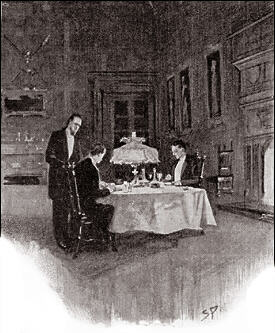

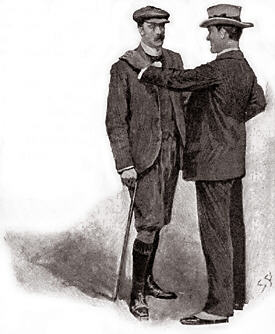

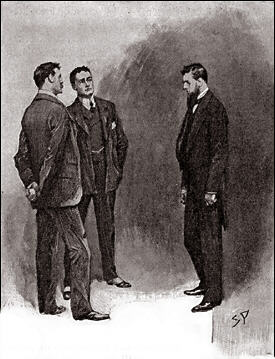

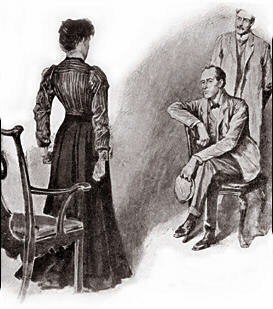

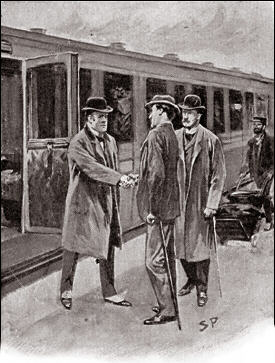

OUR breakfast table was cleared early, and Holmes waited in his dressing-gown for the promised interview. Our clients were punctual to their appointment, for the clock had just struck ten when Dr. Mortimer was shown up, followed by the young baronet. The latter was a small, alert, dark-eyed man about thirty years of age, very sturdily built, with thick black eyebrows and a strong, pugnacious face. He wore a ruddy-tinted tweed suit and had the weather-beaten appearance of one who has spent most of his time in the open air, and yet there was something in his steady eye and the quiet assurance of his bearing which indicated the gentleman.

“This is Sir Henry Baskerville,” said Dr. Mortimer.

“Why, yes,” said he, “and the strange thing is, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, that if my friend here had not proposed coming round to you this morning I should have come on my own

account. I understand that you think out little puzzles, and I’ve had one this morning which wants more thinking out than I am able to give it.”

“Pray take a seat, Sir Henry. Do I understand you to say that you have yourself had some remarkable experience since you arrived in London?”

“Nothing of much importance, Mr. Holmes. Only a joke, as like as not. It was this letter, if you can call it a letter, which reached me this morning.”

He laid an envelope upon the table, and we all bent over it. It was of common quality, grayish in colour. The address, “Sir Henry Baskerville, Northumberland Hotel,” was printed in

rough characters; the post-mark “Charing Cross,” and the date of posting the preceding evening.

“Who knew that you were going to the Northumberland Hotel?” asked Holmes, glancing keenly across at our visitor.

“No one could have known. We only decided after I met Dr. Mortimer.”

“But Dr. Mortimer was no doubt already stopping there?”

“No, I had been staying with a friend,” said the doctor. “There was no possible indication that we intended to go to this hotel.”

“Hum! Someone seems to be very deeply interested in your movements.” Out of the envelope he took a half-sheet of foolscap paper folded into four. This he opened and spread flat upon

the table. Across the middle of it a single sentence had been formed by the expedient of pasting printed words upon it. It ran:

- As you value your life or your reason keep away from the moor.

The word “moor” only was printed in ink.

“Now,” said Sir Henry Baskerville, “perhaps you will tell me, Mr. Holmes, what in thunder is the meaning of that, and who it is that takes so much interest in my

affairs?”

“What do you make of it, Dr. Mortimer? You must allow that there is nothing supernatural about this, at any rate?”

“No, sir, but it might very well come from someone who was convinced that the business is supernatural.”

“What business?” asked Sir Henry sharply. “It seems to me that all you gentlemen know a great deal more than I do about my own affairs.”

“You shall share our knowledge before you leave this room, Sir Henry. I promise you that,” said Sherlock Holmes. “We will confine ourselves for the present with your

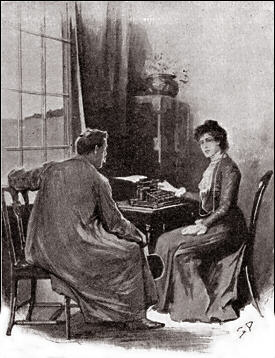

permission to this very interesting document, which must have been put together and posted yesterday evening. Have you yesterday’s Times, Watson?”

“It is here in the corner.”

“Might I trouble you for it–the inside page, please, with the leading articles?” He glanced swiftly over it, running his eyes up and down the columns. “Capital article

this on free trade. Permit me to give you an extract from it.

- “You may be cajoled into imagining that your own special trade or your own industry will be encouraged by a protective tariff, but it stands to reason that such legislation must in the long run keep away wealth from the country, diminish the value of our imports, and lower the general conditions of life in this island.

What do you think of that, Watson?” cried Holmes in high glee, rubbing his hands together with satisfaction. “Don’t you think that is an admirable sentiment?”

Dr. Mortimer looked at Holmes with an air of professional interest, and Sir Henry Baskerville turned a pair of puzzled dark eyes upon me.

“I don’t know much about the tariff and things of that kind,” said he, “but it seems to me we’ve got a bit off the trail so far as that note is

concerned.”

“On the contrary, I think we are particularly hot upon the trail, Sir Henry. Watson here knows more about my methods than you do, but I fear that even he has not quite grasped the

significance of this sentence.”

“No, I confess that I see no connection.”

“And yet, my dear Watson, there is so very close a connection that the one is extracted out of the other. ‘You,’ ‘your,’ ‘your,’ ‘life,’

‘reason,’ ‘value,’ ‘keep away,’ ‘from the.’ Don’t you see now whence these words have been taken?”

“By thunder, you’re right! Well, if that isn’t smart!” cried Sir Henry.

“If any possible doubt remained it is settled by the fact that ‘keep away’ and ‘from the’ are cut out in one piece.”

“Well, now–so it is!”

“Really, Mr. Holmes, this exceeds anything which I could have imagined,” said Dr. Mortimer, gazing at my friend in amazement. “I could understand anyone saying that the words

were from a newspaper; but that you should name which, and add that it came from the leading article, is really one of the most remarkable things which I have ever known. How did you do

it?”

“I presume, Doctor, that you could tell the skull of a negro from that of an Esquimau?”

“Most certainly.”

“But how?”

“Because that is my special hobby. The differences are obvious. The supra-orbital crest, the facial angle, the maxillary curve, the– –”

“But this is my special hobby, and the differences are equally obvious. There is as much difference to my eyes between the leaded bourgeois type of a Times article and the

slovenly print of an evening half-penny paper as there could be between your negro and your Esquimau. The detection of types is one of the most elementary branches of knowledge to the special

expert in crime, though I confess that once when I was very young I confused the Leeds Mercury with the Western Morning News. But a Times leader is entirely

distinctive, and these words could have been taken from nothing else. As it was done yesterday the strong probability was that we should find the words in yesterday’s issue.”

“So far as I can follow you, then, Mr. Holmes,” said Sir Henry Baskerville, “someone cut out this message with a scissors– –”

“Nail-scissors,” said Holmes. “You can see that it was a very short-bladed scissors, since the cutter had to take two snips over ‘keep away.’”

“That is so. Someone, then, cut out the message with a pair of short-bladed scissors, pasted it with paste– –”

“Gum,” said Holmes.

“With gum on to the paper. But I want to know why the word ‘moor’ should have been written?”

“Because he could not find it in print. The other words were all simple and might be found in any issue, but ‘moor’ would be less common.”

“Why, of course, that would explain it. Have you read anything else in this message, Mr. Holmes?”

“There are one or two indications, and yet the utmost pains have been taken to remove all clues. The address, you observe, is printed in rough characters. But the Times is a

paper which is seldom found in any hands but those of the highly educated. We may take it, therefore, that the letter was composed by an educated man who wished to pose as an uneducated one,

and his effort to conceal his own writing suggests that that writing might be known, or come to be known, by you. Again, you will observe that the words are not gummed on in an accurate line,

but that some are much higher than others. ‘Life,’ for example, is quite out of its proper place. That may point to carelessness or it may point to agitation and hurry upon the part

of the cutter. On the whole I incline to the latter view, since the matter was evidently important, and it is unlikely that the composer of such a letter would be careless. If he were in a

hurry it opens up the interesting question why he should be in a hurry, since any letter posted up to early morning would reach Sir Henry before he would leave his hotel. Did the composer fear

an interruption–and from whom?”

“We are coming now rather into the region of guesswork,” said Dr. Mortimer.

“Say, rather, into the region where we balance probabilities and choose the most likely. It is the scientific use of the imagination, but we have always some material basis on which to

start our speculation. Now, you would call it a guess, no doubt, but I am almost certain that this address has been written in a hotel.”

“How in the world can you say that?”

“If you examine it carefully you will see that both the pen and the ink have given the writer trouble. The pen has spluttered twice in a single word and has run dry three times in a short

address, showing that there was very little ink in the bottle. Now, a private pen or ink-bottle is seldom allowed to be in such a state, and the combination of the two must be quite rare. But

you know the hotel ink and the hotel pen, where it is rare to get anything else. Yes, I have very little hesitation in saying that could we examine the waste-paper baskets of the hotels around

Charing Cross until we found the remains of the mutilated Times leader we could lay our hands straight upon the person who sent this singular message. Halloa! Halloa! What’s

this?”

He was carefully examining the foolscap, upon which the words were pasted, holding it only an inch or two from his eyes.

“Well?”

“Nothing,” said he, throwing it down. “It is a blank half-sheet of paper, without even a water-mark upon it. I think we have drawn as much as we can from this curious letter;

and now, Sir Henry, has anything else of interest happened to you since you have been in London?”

“Why, no, Mr. Holmes. I think not.”

“You have not observed anyone follow or watch you?”

“I seem to have walked right into the thick of a dime novel,” said our visitor. “Why in thunder should anyone follow or watch me?”

“We are coming to that. You have nothing else to report to us before we go into this matter?”

“Well, it depends upon what you think worth reporting.”

“I think anything out of the ordinary routine of life well worth reporting.”

Sir Henry smiled.

“I don’t know much of British life yet, for I have spent nearly all my time in the States and in Canada. But I hope that to lose one of your boots is not part of the ordinary

routine of life over here.”

“You have lost one of your boots?”

“My dear sir,” cried Dr. Mortimer, “it is only mislaid. You will find it when you return to the hotel. What is the use of troubling Mr. Holmes with trifles of this

kind?”

“Well, he asked me for anything outside the ordinary routine.”

“Exactly,” said Holmes, “however foolish the incident may seem. You have lost one of your boots, you say?”

“Well, mislaid it, anyhow. I put them both outside my door last night, and there was only one in the morning. I could get no sense out of the chap who cleans them. The worst of it is that

I only bought the pair last night in the Strand, and I have never had them on.”

“If you have never worn them, why did you put them out to be cleaned?”

“They were tan boots and had never been varnished. That was why I put them out.”

“Then I understand that on your arrival in London yesterday you went out at once and bought a pair of boots?”

“I did a good deal of shopping. Dr. Mortimer here went round with me. You see, if I am to be squire down there I must dress the part, and it may be that I have got a little careless in my

ways out West. Among other things I bought these brown boots–gave six dollars for them–and had one stolen before ever I had them on my feet.”

“It seems a singularly useless thing to steal,” said Sherlock Holmes. “I confess that I share Dr. Mortimer’s belief that it will not be long before the missing boot is

found.”

“And, now, gentlemen,” said the baronet with decision, “it seems to me that I have spoken quite enough about the little that I know. It is time that you kept your promise and

gave me a full account of what we are all driving at.”

“Your request is a very reasonable one,” Holmes answered. “Dr. Mortimer, I think you could not do better than to tell your story as you told it to us.”

Thus encouraged, our scientific friend drew his papers from his pocket and presented the whole case as he had done upon the morning before. Sir Henry Baskerville listened with the deepest

attention and with an occasional exclamation of surprise.

“Well, I seem to have come into an inheritance with a vengeance,” said he when the long narrative was finished. “Of course, I’ve heard of the hound ever since I was in

the nursery. It’s the pet story of the family, though I never thought of taking it seriously before. But as to my uncle’s death–well, it all seems boiling up in my head, and I

can’t get it clear yet. You don’t seem quite to have made up your mind whether it’s a case for a policeman or a clergyman.”

“Precisely.”

“And now there’s this affair of the letter to me at the hotel. I suppose that fits into its place.”

“It seems to show that someone knows more than we do about what goes on upon the moor,” said Dr. Mortimer.

“And also,” said Holmes, “that someone is not ill-disposed towards you, since they warn you of danger.”

“Or it may be that they wish, for their own purposes, to scare me away.”

“Well, of course, that is possible also. I am very much indebted to you, Dr. Mortimer, for introducing me to a problem which presents several interesting alternatives. But the practical

point which we now have to decide, Sir Henry, is whether it is or is not advisable for you to go to Baskerville Hall.”

“Why should I not go?”

“There seems to be danger.”

“Do you mean danger from this family fiend or do you mean danger from human beings?”

“Well, that is what we have to find out.”

“Whichever it is, my answer is fixed. There is no devil in hell, Mr. Holmes, and there is no man upon earth who can prevent me from going to the home of my own people, and you may take

that to be my final answer.” His dark brows knitted and his face flushed to a dusky red as he spoke. It was evident that the fiery temper of the Baskervilles was not extinct in this their

last representative. “Meanwhile,” said he, “I have hardly had time to think over all that you have told me. It’s a big thing for a man to have to understand and to

decide at one sitting. I should like to have a quiet hour by myself to make up my mind. Now, look here, Mr. Holmes, it’s half-past eleven now and I am going back right away to my hotel.

Suppose you and your friend, Dr. Watson, come round and lunch with us at two. I’ll be able to tell you more clearly then how this thing strikes me.”

“Is that convenient to you, Watson?”

“Perfectly.”

“Then you may expect us. Shall I have a cab called?”

“I’d prefer to walk, for this affair has flurried me rather.”

“I’ll join you in a walk, with pleasure,” said his companion.

“Then we meet again at two o’clock. Au revoir, and good-morning!”

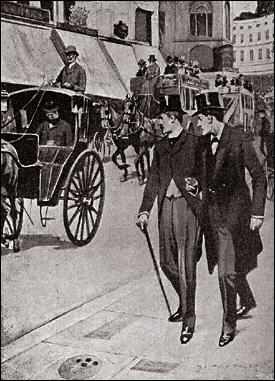

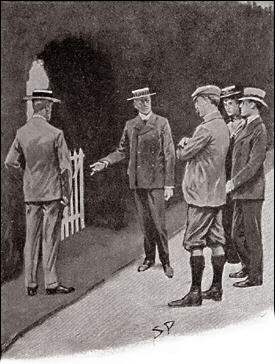

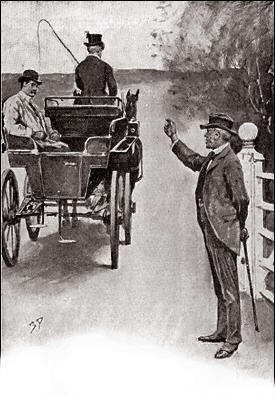

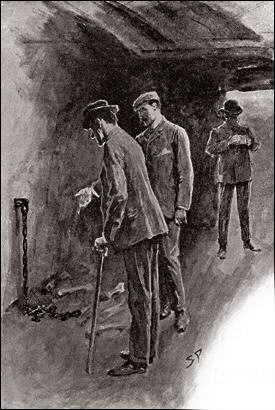

We heard the steps of our visitors descend the stair and the bang of the front door. In an instant Holmes had changed from the languid dreamer to the man of action.

“Your hat and boots, Watson, quick! Not a moment to lose!” He rushed into his room in his dressing-gown and was back again in a few seconds in a frock-coat. We hurried together down

the stairs and into the street. Dr. Mortimer and Baskerville were still visible about two hundred yards ahead of us in the direction of Oxford Street.

“Shall I run on and stop them?”

“Not for the world, my dear Watson. I am perfectly satisfied with your company if you will tolerate mine. Our friends are wise, for it is certainly a very fine morning for a

walk.”

He quickened his pace until we had decreased the distance which divided us by about half. Then, still keeping a hundred yards behind, we followed into Oxford Street and so down Regent Street.

Once our friends stopped and stared into a shop window, upon which Holmes did the same. An instant afterwards he gave a little cry of satisfaction, and, following the direction of his eager

eyes, I saw that a hansom cab with a man inside which had halted on the other side of the street was now proceeding slowly onward again.

“There’s our man, Watson! Come along! We’ll have a good look at him, if we can do no more.”

At that instant I was aware of a bushy black beard and a pair of piercing eyes turned upon us through the side window of the cab. Instantly the trapdoor at the top flew up, something was

screamed to the driver, and the cab flew madly off down Regent Street. Holmes looked eagerly round for another, but no empty one was in sight. Then he dashed in wild pursuit amid the stream of

the traffic, but the start was too great, and already the cab was out of sight.

“There now!” said Holmes bitterly as he emerged panting and white with vexation from the tide of vehicles. “Was ever such bad luck and such bad management, too? Watson,

Watson, if you are an honest man you will record this also and set it against my successes!”

“Who was the man?”

“I have not an idea.”

“A spy?”

“Well, it was evident from what we have heard that Baskerville has been very closely shadowed by someone since he has been in town. How else could it be known so quickly that it was the

Northumberland Hotel which he had chosen? If they had followed him the first day I argued that they would follow him also the second. You may have observed that I twice strolled over to the

window while Dr. Mortimer was reading his legend.”

“Yes, I remember.”

“I was looking out for loiterers in the street, but I saw none. We are dealing with a clever man, Watson. This matter cuts very deep, and though I have not finally made up my mind whether

it is a benevolent or a malevolent agency which is in touch with us, I am conscious always of power and design. When our friends left I at once followed them in the hopes of marking down their

invisible attendant. So wily was he that he had not trusted himself upon foot, but he had availed himself of a cab so that he could loiter behind or dash past them and so escape their notice.

His method had the additional advantage that if they were to take a cab he was all ready to follow them. It has, however, one obvious disadvantage.”

“It puts him in the power of the cabman.”

“Exactly.”

“What a pity we did not get the number!”

“My dear Watson, clumsy as I have been, you surely do not seriously imagine that I neglected to get the number? No. 2704 is our man. But that is no use to us for the moment.”

“I fail to see how you could have done more.”

“On observing the cab I should have instantly turned and walked in the other direction. I should then at my leisure have hired a second cab and followed the first at a respectful

distance, or, better still, have driven to the Northumberland Hotel and waited there. When our unknown had followed Baskerville home we should have had the opportunity of playing his own game

upon himself and seeing where he made for. As it is, by an indiscreet eagerness, which was taken advantage of with extraordinary quickness and energy by our opponent, we have betrayed ourselves

and lost our man.”

We had been sauntering slowly down Regent Street during this conversation, and Dr. Mortimer, with his companion, had long vanished in front of us.

“There is no object in our following them,” said Holmes. “The shadow has departed and will not return. We must see what further cards we have in our hands and play them with

decision. Could you swear to that man’s face within the cab?”

“I could swear only to the beard.”

“And so could I–from which I gather that in all probability it was a false one. A clever man upon so delicate an errand has no use for a beard save to conceal his features. Come in

here, Watson!”

He turned into one of the district messenger offices, where he was warmly greeted by the manager.

“Ah, Wilson, I see you have not forgotten the little case in which I had the good fortune to help you?”

“No, sir, indeed I have not. You saved my good name, and perhaps my life.”

“My dear fellow, you exaggerate. I have some recollection, Wilson, that you had among your boys a lad named Cartwright, who showed some ability during the investigation.”

“Yes, sir, he is still with us.”

“Could you ring him up?–thank you! And I should be glad to have change of this five-pound note.”

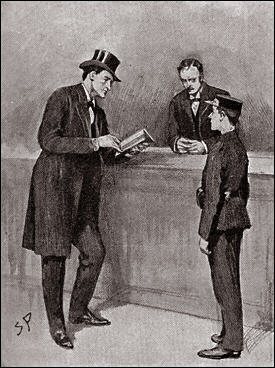

A lad of fourteen, with a bright, keen face, had obeyed the summons of the manager. He stood now gazing with great reverence at the famous detective.

“Let me have the Hotel Directory,” said Holmes. “Thank you! Now, Cartwright, there are the names of twenty-three hotels here, all in the immediate neighbourhood of Charing

Cross. Do you see?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You will visit each of these in turn.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You will begin in each case by giving the outside porter one shilling. Here are twenty-three shillings.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You will tell him that you want to see the waste-paper of yesterday. You will say that an important telegram has miscarried and that you are looking for it. You understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

“But what you are really looking for is the centre page of the Times with some holes cut in it with scissors. Here is a copy of the Times. It is this page. You could

easily recognize it, could you not?”

“Yes, sir.”

“In each case the outside porter will send for the hall porter, to whom also you will give a shilling. Here are twenty-three shillings. You will then learn in possibly twenty cases out of the twenty-three that the waste of the day before has been burned or removed. In the three other cases you will be shown a heap of paper and you will look for this page of the Times among it. The odds are enormously against your finding it. There are ten shillings over in case of emergencies. Let me have a report by wire at Baker Street before evening. And now, Watson, it only remains for us to find out by wire the identity of the cabman, No. 2704, and then we will drop into one of the Bond Street picture galleries and fill in the time until we are due at the hotel.”

THREE BROKEN THREADS

SHERLOCK HOLMES had, in a very remarkable degree, the power of detaching his mind at will. For two hours the strange business in which we had been involved

appeared to be forgotten, and he was entirely absorbed in the pictures of the modern Belgian masters. He would talk of nothing but art, of which he had the crudest ideas, from our leaving the

gallery until we found ourselves at the Northumberland Hotel.

“Sir Henry Baskerville is upstairs expecting you,” said the clerk. “He asked me to show you up at once when you came.”

“Have you any objection to my looking at your register?” said Holmes.

“Not in the least.”

The book showed that two names had been added after that of Baskerville. One was Theophilus Johnson and family, of Newcastle; the other Mrs. Oldmore and maid, of High Lodge, Alton.

“Surely that must be the same Johnson whom I used to know,” said Holmes to the porter. “A lawyer, is he not, gray-headed, and walks with a limp?”

“No, sir, this is Mr. Johnson, the coal-owner, a very active gentleman, not older than yourself.”

“Surely you are mistaken about his trade?”

“No, sir! he has used this hotel for many years, and he is very well known to us.”

“Ah, that settles it. Mrs. Oldmore, too; I seem to remember the name. Excuse my curiosity, but often in calling upon one friend one finds another.”

“She is an invalid lady, sir. Her husband was once mayor of Gloucester. She always comes to us when she is in town.”

“Thank you; I am afraid I cannot claim her acquaintance. We have established a most important fact by these questions, Watson,” he continued in a low voice as we went upstairs

together. “We know now that the people who are so interested in our friend have not settled down in his own hotel. That means that while they are, as we have seen, very anxious to watch

him, they are equally anxious that he should not see them. Now, this is a most suggestive fact.”

“What does it suggest?”

“It suggests–halloa, my dear fellow, what on earth is the matter?”

As we came round the top of the stairs we had run up against Sir Henry Baskerville himself. His face was flushed with anger, and he held an old and dusty boot in one of his hands. So furious

was he that he was hardly articulate, and when he did speak it was in a much broader and more Western dialect than any which we had heard from him in the morning.

“Seems to me they are playing me for a sucker in this hotel,” he cried. “They’ll find they’ve started in to monkey with the wrong man unless they are careful. By thunder, if that chap can’t find my missing boot there will be trouble. I can take a joke with the best, Mr. Holmes, but they’ve got a bit over the mark this time.”

“Still looking for your boot?”

“Yes, sir, and mean to find it.”

“But, surely, you said that it was a new brown boot?”

“So it was, sir. And now it’s an old black one.”

“What! you don’t mean to say– –?”

“That’s just what I do mean to say. I only had three pairs in the world– the new brown, the old black, and the patent leathers, which I am wearing. Last night they took one of my brown ones, and to-day they have sneaked one of the black. Well, have you got it? Speak out, man, and don’t stand staring!”

An agitated German waiter had appeared upon the scene.

“No, sir; I have made inquiry all over the hotel, but I can hear no word of it.”

“Well, either that boot comes back before sundown or I’ll see the manager and tell him that I go right straight out of this hotel.”

“It shall be found, sir–I promise you that if you will have a little patience it will be found.”